The eye is the lamp of the body. If your eyes are good, your whole body will be full of light. But if your eyes are bad, your whole body will be full of darkness. If then the light within you is darkness, how great is that darkness! (Matt. 6:22-23, NIV)

Every art and every inquiry, and similarity every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good; and for this reason the good has been rightly declared to be that at which all things aim. (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics)

To save you from reading this whole post, I’ll start by immediately disclosing the curriculum our family has chosen and then proceed with our justification, in an attempt to ensure that you might glean from our decision making process rather than simply to advertise for our curriculum, which we so far like very much.

For Elijah’s Second Grade year we’ve decided to work through Moving Beyond the Page, and have chosen the curriculum for ages 7-9 for English Language arts, Social Sciences and Science, but ages 6-8 for math.

And now for the journey...

For the last two years I’ve been intrigued by the work done for decades by Veritas Press. They have made available to the Home Education community a Classical curriculum that is approachable and enriching, and I do like a classical education.

The classical education provided through Veritas employs what they call the Trivium, a three-stage approach to grades K-12 that begins with learning how to learn in the “Grammar Stage”. Children begin learning Latin and the basics of how to lean efficiently, all through reading rich texts and memory chants and jingles. The form of the education for this first stage is mostly memorization; Veritas rightly observes that, "at this stage, young children are naturally inquisitive and are both willing and able to memorize and recite lots of material," and so the curriculum sort of sneak-attacks the malleable minds with historical timelines and latin exercise designed to be fun and to lay a foundation for further study.

The Veritas curriculum continues to the Logic stage (roughly grades 7-10) during which students begin to learn how to put together the information they've absorbed in the grammar stage and begin forming arguments. Lastly, students enter the Rhetoric stage in which they make use of the knowledge that has now expanded and deepened from the Grammar stage and the work they've done in understanding thought to make arguments from the Logic stage. Students are called to analyze and create in this stage.

To some extent, Veritas follows Aristotle's understanding of education, especially his understanding of the developmental stages of a student and her progress through them (you'll be able to read more about this when I write about Piaget, who also argues that understanding developmental stages is crucial to education). And while I see the value in adhering to Aristotelian stages — to which Veritas adheres loosely — I think that Aristotle is at his best when he discusses education as a formation of the whole person: education for Aristotle was a practice of developing habits that enabled living the Good Life.

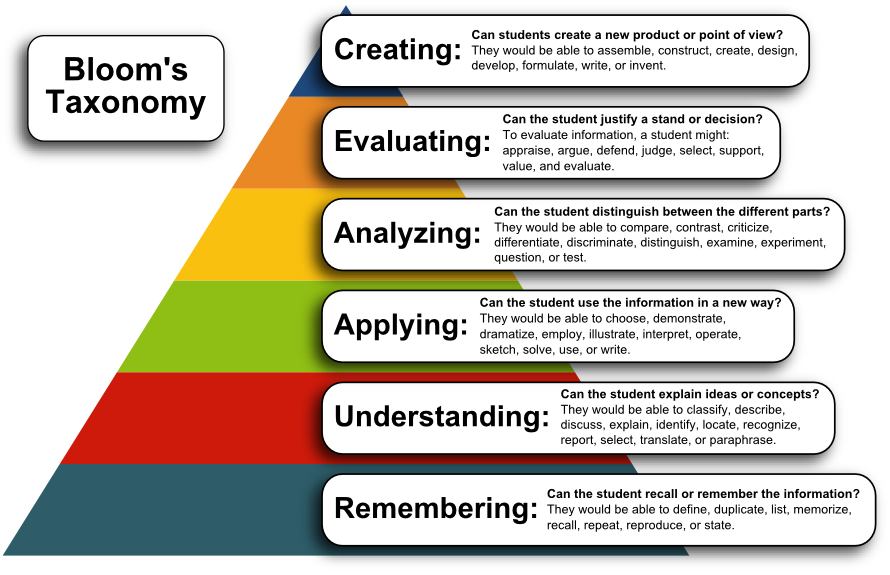

This staged approach to learning is also present in contemporary educational research in the form of Bloom’s Taxonomy and Piaget’s stages of development, both of which I will cover in future posts, the former on assessments and the latter on Vygotsy and Piaget.

Most people who spend time to study education observe that learning happens in some kinds of distinct stages and I’m quite sure that this is why there are no three synoptic gospels and one Johanine one: Jesus knows that the human mind needs to taught in some kind of deliberate and systematic way. The New Testament follows this pattern — the Gospels which introduce us to the deep things of Jesus, then, in a sort deliberately different repetition, acquaint the reader with Jesus’ life, deepening and ripening in the knowledge of Him through John’s Gospel. The Epistles apply the new life that Jesus introduced. This is rough and really bares more study (still another post) but for now I think I’ve shown that Jesus, through the Holy Spirit, teaches us in a structured way — first we see men as trees walking, then we see real men, then we can see Jesus for who He is.

I introduce this now because I think it’s a really, really important concept for us, as Home Educators, to let sink deep into our hearts, so deep that it characterizes our interaction with our children whether teaching a lesson or taking a walk. And I want to begin thinking about it through Bloom’s Taxonomy. Bloom argued that knowledge enters into the mind following a relatively predectible path. We begin identifying that knowledge exists in his “Knowledge” stage, and move through the “Evaluate” stage, in which we form well informed opinions and unique ideas about the the knowledge and how if fits into the world around us. There are modifications, additions, and subtractions to this process, but for the most part it looks something like this:

You’ll see that even in the example I give there is a variant — instead of ending with “Evaluation” this chart ends in “Create”. Instead of explaining what happened, I’ll leave you with a question: What would be the value of ending with “Creating” instead of “Evaluation”? Is knowledge most internalized when a person can evaluate it or create with it? It might be crude to think of a walk with Jesus beginning in the “Knowledge” phase and ending in the “Create” phase, but I also think there’s something to it — and if there is, what do “Knowledge” and “Creating” look like in our Christian lives?

While I would love to spend pages showing examples from the classroom about how Bloom’s taxonomy works, for now, I don't want to diverge too far from a discussion on curriculum.

So I return:

While Jen and I really liked the rigor and structure of Veritas, we were confronted with choosing Elijah's curriculum in the middle of the

Black Lives Matter movement and, although the

Veritas curriculum is rich and profound in history and knowledge, it is also richly and profoundly Eurocentric and white, which means that it is also predominantly male. Most of the texts assigned through Veritas are written by white men, and about white people. If we apply Aristotle's principle that education should instill in students what it means to live the good life, and we willingly select a curriculum populated largely by white males, we are at least in part (and perhaps more than in part) communicating to Elijah that the best way to pursue the good life is to be white and male.

So it is that Veritas, despite its many, many virtues, could not articulate with some of deepest my educational convictions.

Additionally, we've been blessed with a son who has a passion for the scientific. Elijah has developed a passion for engineering primarily through the somewhat obscure Robo-sport, Battlebots. He also has an insatiable curiosity about the natural world around him, having memorized the planets early on, and even now choosing books and tv shows produced by National Geographic more than just about anything else.

This presented a challenge in choosing from home school curricula, most of which are exhibit a particular deficit in (allergy to?) science and math instruction.

Finding a curriculum that supports Elijah's interest in engineering and science is further complicated by my relative lack of interest therein and my insistence that — somewhat against Aristotle's categories — knowledge cannot be so delineated as to speak about really distinct disciplines. Good thinking in writing, I’m convinced, shares in good thinking about mathematics; the transitive properties of addition and multiplication have no real meaning apart from a person's ability to explain such things, just as a person's insistence on a round earth, or vaccinating their children, or to wear a mask during a pandemic, have no real meaning apart from a person's ability to justify those actions (and while the stuff of justification is, alas, a topic for another post, I do want to insist that simply stating a logical argument is not justification enough; rather, we must be able to align our actions to the image of Christ developing in us through the work of the Holy Spirit, and if you're wondering how transitivity relates to my and your development in Christ, I'm happy to share that...at a later date).

This is an important point so I don’t want it to be lost in my above mentioned hot-button issues. Thinking well and communicating those well formed thoughts are crucial to the Christian call, and crucial to human existence. It is not excusable for an engineer to be inarticulate because she could easily miscommunicate some important specifications. Conversely, it is not excusable for a poet to be ignorant of the workings of creation because it will lead to impassioned misinformation about how the world works. The Scriptures in their Holy Inspiration, contain accurate and beautiful illustrations that communicate deep, deep meaning about how all of creation works. Think about Jesus’ pastoral (pasture, not pastor) parables which understand sheep and goats and birds and lilies and seed and vines so well. As Christians we are called to know well the observations of science, think deeply about them, and in them, through the work of the Holy Spirit, know Our Lord more fully.

For many home school curricula, when they incorporate science and mathematics, they're incorporated largely in the same way that traditional schools do so: as some sort of educational addendum. Math has a separate book that either betrays the educational philosophy of the rest of the curriculum or else it attempts to adapt Singapore or Saxon Math which share some of the educational principles that lead us to home schooling, but aren't necessarily homogenous with the curriculum.

This similarly applies to the many and varied Home School curricula's treatments of science: it is an added elective, an afterthought and a distant second or third seat to reading and writing. This is a deficit that simply won’t do in our house - especially because Jen is an engineer - and it shouldn’t do for yours either, whether you are a family of engineers or poets. As stewards of His creation, the Lord has called us to know His creation and speak fluently about it well.

This isn't to say that I am a proponent of the

very popular STEM movements that have swept our land. These tend to prioritize a breed of education that produces chestless people and perpetuate an emphasis on the fiscal necessity of education: it argues, "what good is reading stories when you cannot make money doing so?" In short, America's insistence on a STEM based curriculum has appropriated the public education system for economic gain, in a way transforming all of American education into a trade school for the future Googles, Microsofts, and JPLs.

So what would a Via Media look like? How can we prioritize Science and Mathematics while teaching our students that over and above the memorization and execution of scientific and mathematic principles for economic gain, humans are called to live the good life (which Christians understand that as a life surrendered to Christ)?

The answer lies in an integrated curriculum that doesn't divorce habits of thought from one another. This would be curriculum that teaches math through math's necessity — a task that word problems attempt to approximate, but fail, I think, to accomplish — in actual, real life inquiry, inspired by the exploration of God's creation, especially through literature. In other words, students would read books and stories and poems to expand their perspectives and experiences while using Language Arts, Math, Science and Social Science to help describe their own experiences. The pursuit of the good life becomes the point of coalescence for the disciplines, it becomes the master discipline and, therethrough, demands that all the disciplines surrender to it.

Students might begin by exploring the weather, as Elijah's first concept does through Moving Beyond the Page. During his Language Arts lessons, we read books that illustrate the interactions between Earth's Weather Systems and human beings. This leads toward him observing the weather around us and keeping a weather journal (a practice that everyone in the family has committed to do), the creation of his own barometer, and eventually equipping him with the tools for predicting the weather. But none of this is done without first reading a book of stories about a dog titularly named Tornado that illustrates the impact of weather on humans. Ideally math lessons would be driven by the necessity of measuring the components of the barometer, finding averages for the sake of weather prediction, measuring differences to show degrees of change, etc. Admittedly Moving Beyond the Page does not do this though as a home educator, I can facilitate this sort of natural integration if only for reenforcement.

In this model, math, science, social sciences, and language arts all serve The Good, the purpose of education. And from the Christian perspective, The Good is a the Zoe Life, the abundant life of John 10:10. We are called to love God with all of our hearts, souls, all of our minds, all of our strength. The unifying force in education is the ends for which educate: knowing God and understanding our place as stewards of His creation.

And so, Jen and I have chosen a curriculum which is texts based like a classical curriculum, but includes Science and Social Sciences in an integrated way, and which limits the amount of tests, but instead relies on projects for assessments.

I don't want our curriculum choice to stand as an argument for Moving Beyond the Page especially because we haven't actually taught through the thing yet. Rather, I hope that I've given you a means by which you can make the choice for your family and your student's needs. And so I'll summarize this in 6 Steps. These are adapted from the steps that I use to determine the effectiveness of a classroom lesson or unit:

- First, determine the things that excite your child and your family about education and ensure that your curriculum highlights those things. It might be art, or exploration, or music, but whatever it is educating from a passion will generate in your student(s) the curiosity and excitement that drive our desire to know more about the world the Lord has made.

- Consider your student's skill levels. Some kids read better than others. You've got to be honest about this. Elijah, for instance, will be learning math in an age range lower than his other subjects. Your student is learning and will very likely become more proficient than she would in traditionally schooling, but you've got to know where to start (for more on this, read my forthcoming post on Yygotsky and Zones of Proximal Development).

- Identify and articulate your "good". Turn right now to the person in sitting next to you or open a word processor or a notes app on your phone at begin with "I think the main purpose of education is _________. And I think this because ____________." You might disagree with me that a curriculum containing almost exclusively texts from white European men perpetuates a culture of power that has plagued Western civilization to the exclusion of the gospel (though you shouldn't), but you do have some convictions about education that you won't realize until you begin saying or writing them.

- Consider the state standards in your area. We live in California which adheres to Common Core and, while I know there are (were?) many ill feelings towards Common Core, I plan to make an argument in another post that state standards are not the boogey man and shouldn't be treated as such. You'll want to be aware of the Standards because situations in life change and there is a possibility that you won't always be educating your children at home. For their sake, you'll want to ensure throughout their education that they are compliant with the standards.

- Discover the cost. I haven't mentioned the cost of the curriculum and materials we chose because it didn't weigh into our decision, but it might do so for you. Remember that most of the curriculum options have offer financing and the ability to pay for one semester at time.

- Differentiate instruction for your child. In the traditional classroom setting, one of the finest and most complicated skills is differentiating instruction, or supplying enough different windows into the house of you lesson plans so that anyone sitting in the classroom — regardless of cultural heritage, language proficiency, or skill level — can access the core information you are trying to communicate. In other words, you’ve got to know your children well. If the reading, writing, and memorizing necessary for a classical education simply doesn’t seem to excite your children, don’t insist on it just because it’s what other people do. Or, more accurately, don’t do it exclusively. Our curriculum, for instance, is advertised as being great for secular families who want to home school. I’ll adjust instruction to ensure that we integrate a Christian worldview throughout because Moving Beyond the Page is in almost every other way perfect for Elijah’s learning styles and interest.

There are other questions that you'll want to answer that I haven't included because, as I've said, I'm adapting this list from my lesson planning tool.

Once you've answered these questions you'll want to look through the available curricula and see what deficits exist — and there will be deficits for every curriculum — before you choose. I’ll do my best to supply my favorite here, but would honestly be mostly doing google searches to include anything beyond these three:

- Veritas

- Moving beyond the page

- Ambleside

I’ll be doing my best to include in Elijah’s learning the best of these three, keeping the core of Moving Beyond the Page.

Lastly, I’ll say that the state of California requires that your child attend school for a total of 180 days, but the state doesn’t say what you have to do with those days. If you have a couple of false starts, don't fret; you can and most certainly will make that time up by dedicating the sort of attention to your students that classroom teachers simply cannot; you can’t view as wasted any time you spend fumbling with the material — kids learn even through our mistakes. We serve our children best by showing them that we are taking their education seriously enough to choose the correct curriculum for them.

Comments

Post a Comment